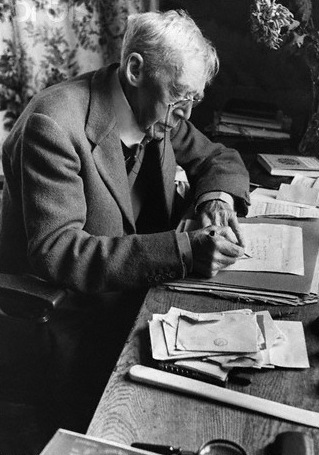

Murder your darlings is a phrase that was first used by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch (the dapper gent illustrated here) in a 1914 lecture on writing style at Cambridge University. What it means is probably best put by saying that if you think you’ve written something especially clever and particularly witty in a turn of phrase whose inner beauty will have the gods themselves weeping with joy, then it almost certainly needs to be deleted and should, on no account, be printed.

Murder your darlings is a phrase that was first used by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch (the dapper gent illustrated here) in a 1914 lecture on writing style at Cambridge University. What it means is probably best put by saying that if you think you’ve written something especially clever and particularly witty in a turn of phrase whose inner beauty will have the gods themselves weeping with joy, then it almost certainly needs to be deleted and should, on no account, be printed.

Harsh? Possibly. But it is a very useful guide when you are new to writing (when you are naturally more prone to making these errors), and it has the additional advantage of inuring you somewhat to the pain and anguish of having your deathless prose work edited, redacted, and generally stomped all over by everyone who comes after you in the process.

Whilst this phrase and principle is literary in origin, it applies just as much to games design.

Very often novice designers, like novice writers, will announce that they have finished with a project when in reality it still needs some cutting back. This is partly the understandable side-effect of enthusiasm and inexperience, and I did it as much as anyone. I still do, on occasion, though less so now I have a better understanding and more experience and I am often able to purge my own work before someone else has to. Now I know there is a trap, I can avoid it more easily. Eventually practice may make perfect, though I think I’m a long way off yet.

Applying this notion is fairly simple in principle, and hard in practice, as so many things are. First, you have to design your game, or at least make a start. Then, you have to see if any darlings need a quiet knife in the back. Ideally, you should do this as you go along. That way you can clear up any mess as you make it.

Applying this notion is fairly simple in principle, and hard in practice, as so many things are. First, you have to design your game, or at least make a start. Then, you have to see if any darlings need a quiet knife in the back. Ideally, you should do this as you go along. That way you can clear up any mess as you make it.

The big question is how do you know what is a darling? The best way I have found is by asking yourself which bits are your cleverest. You may have a workmanlike movement system, and a set of stats which is near-universal, but at one side you have a cunningly wrought rules engine that includes all manner of clever modifiers and twists. You are most proud of its cunning and elegance. It could be your masterpiece, or it could be vainglorious nonsense. Ask yourself: is it really necessary, or is it being clever just to show off? Try taking it out or putting a much simpler system in its place. Does the game still work? What did you lose? Ask other playtesters. Did they notice the difference? Removing some rules will bring the whole edifice down, and others will disappear entirely unnoticed. These latter rules should be high on your list to die. Of course, it may really be clever and elegant. Novices can write just as great stuff as veterans. But not always.

As you gain experience you will learn to use the principle routinely, but even then it is worthwhile consciously stopping and taking stock every now and again. Read your manuscript. Is it all really worth keeping? Can you excise that rule? It’s ever so clever, but does that alone warrant it’s inclusion?

If at all possible, you will be greatly helped by putting a project to one side and leaving it alone for as long as possible. Fresh eyes are what is needed, and you will benefit from a break if you can afford the time. When you come back to it, read the whole thing from scratch, just as if you were coming to it for the first time. Are the rules clearly explained? Do any bits jump out or jar. Often a darling will be obvious by being in a different style of writing, or in a different style of rule (if you see what I mean). Try playing it again, preferably with someone who did not help you develop it this far. Are there any bits that seem redundant, or which would lose little, but help the whole thing to be more streamlined? A particularly big clue is when a rule seems brilliant to you, but incomprehensible or irrelevant to others.

Of course, this is only one of a myriad reasons why games are not always as good as they could be. Time and money considerations are critical drivers and most projects get less playtesting with less critical gamers than they really need. Still, learning how to murder your darlings is a simple and easily applicable concept that can help make your game better, whatever your budget. If you write or design anything, then I’d urge you to give it a go.

This is extremely good advice !

I have used it time and again, and still do routinely, for every creative work I undertake. It works just as well for RPG scenarios :

Is this NPC just there for show, or does he actually do something for the story ? NPCs you love and don’t want to kill, or seem unkillable (and you sometimes love them because they’re former PCs of yours), are prime suspects for your black list of darlings to eliminate.

Is this place with these customs and these people actually indispensable to the plot, or could you drop it ? Try trimming some of the dead wood… What did you lose ? Did you lose atmosphere where it was needed, or is the substance of the plot elements actually more acute now that you can see them better ? Is that fight really necessary, or is it breaking the pace ?

All those questions and many more that you can ask yourself when you’re writing for game night… Or when you’re just plain writing, actually… Mutatis mutandis.

“Mutatis mutandis”… a phrase from a bio-engineer’s logbook if ever I heard one.

Pingback: Design Theory: Less Is More | quirkworthy

Sounds very familiar!!!

I always try to apply KISS. And if it is too complicated for my testgroups it needs another round of KISS. Sometimes designers are like parents that cannot let go of theri favourite child, i.e. they cling to certain mechanics that were possibly brilliant in the beginning, but no hamper the game more than they help.

KISS is another old favourite, though not one I consciously use much myself. I think there are times when rules should be quite involved – it’s just a matter of judgement.

The other possibility is that the rule is fine, but it is not explained clearly enough. I’m sure we can all think of games where that is true.

I kind of already do this without having run into this specific philosophy, when doing blog posts, but I find I go rabbit-in-the-headlights and don’t put anything up public until I’ve iterated it several times, by which point, it’s out of date. I’m similar, but much less cripplingly so, with painting.

I’ve talked about this very same topic myself a few months back, but from a writers perspective. When I first started writing (over 12 years ago now) the first draft in my mind was great. Perfection. Done and dusted, I started sending it out to prospective buyers and publishers and then felt perplexed when all I got back were rejection slips. It took a few years to learn, but that initial draft is just an idea. Anyone can do that, write a script or a novel, or design a game etc. The REAL work comes in the rewrites. That’s where the magic truly happens. And yes, it may sometimes mean killing your darlings. For me that could be a whole scene, a line of dialogue or maybe even entire subplots, but what is important is the story. If that line doesn’t serve the story – out it goes. If that particular character slows the pace down and doesn’t add anything – SCHNIKK! – one slit throat and we’re sorted.

It’s like an archaeologist uncovering a fossil. At first its a great lump of clay, but by brushing away the extraneous layers, removing the excess waste, slowly, very slowly in some cases, the true beauty is revealed.

I am also a big supporter of the KISS rule (again, another post was written all about this subject as well many moons ago). If it’s simple in concept there is a greater chance it will be more elegant in practice – not as many parts to break. It is a practice I use every day whether I’m writing a script, short story or, as is now, a novel.

Pingback: Review: Carnevale – Rhinos Can’t Jump! | quirkworthy

Pingback: Tribes Of Legend – Update | quirkworthy

Pingback: Dreadfleet Salvage Project – Version 1.0 |

Pingback: Design Theory: Simplicity vs Dumbing Down |

I dont seem to work the same as you more artisticaly talented folk.

I tend to start with the minimum that I can get a way with to arrive at function.

Then try to add on character and theme.And this is where it all goes pear shaped!

I realy WINCE at the games with lots of needless over complication like 40k.

But seem to toaly mis judge where the ‘sweet spot’ is for the ‘overcomplication to get more character’, gamers appear to need?

‘Where are all the special rules? ‘they ask.

‘There are special abilities , that are included in the core rules.. ‘ I say.

‘Ahh ,but they are not ‘special rules’ that make the army,units,models ‘special’ ‘.

‘You mean exceptions to the core rules/additional rules,( that make the rules unessisarily over complicated)?’

‘Yeah thats them.’

‘You do know you dont actualy need them right?’

‘Well why do all the other games I know of have them then…’

‘I have no idea…’

Can anyone enlighten me?

(Its like when my wife expects me to say how nice she looks when trying on dresses.How honest -how tactful ,how can you win!)

See my reply to the comment below.

Also, I’d say that it’s partly style and taste, so there isn’t a right answer. It’s also to do with expectation. People in general aren’t good at new and unexpected, and will happily have poorer quality things if they are comfortable and familiar. Not just in gaming either.

Pingback: Did They Deserve To Die? |

Getting off on tangent here, but I just hate game design by exception.

IMHO, every “special rule” is just testament to the original design’s failure. The designer failed to make the core rules varied and interesting and is trying to compensate by adding bits and bobs here and there… my litmus test for rules is trying just the basic rules with two identical forces. If the game is still interesting, there might be something there…

It depend on what you’re trying to design, and where you want your complexity.

Let’s say you’re designing a tabletop miniatures game with 6 or 8 or more factions, each with 20+ different troop types and potential variations within that for weapons or equipment PLUS you want them to be able to grow and change with experience in a campaign.

If you use the special rules model then you can have a very simple stat line of perhaps 3 or 4 values. This is enough to give you the core variation, but it is not sufficient to cover the whole range. The intent of special rules, as a concept, is to only include a rule where it is needed. In some systems I’ve seen (and what you seem to be promoting) every model has a massive stat line, much of which is not used by an individual model. In other words, every model carries around a great overburden of useless rules simply because someone does need it – quite possibly someone who is not even in this particular battle. I find that messy, bloated and very easy to forget because in order to play I’ve got to remember a whole bunch of stuff that almost never actually does anything. My mind rebels against memorising stuff it knows is pointless.

The big advantage of using special rules is that the stats and rules have a purpose when they are listed and are invisible when they are not. That makes the design far slicker and much easier to remember. If it’s on the model then it’s there for a reason and will be used for that model in this game. It’s not just dead weight.

Of course, if we’re talking about abstract board games then there are different expectations and also far fewer variations in playing piece. Typically you’ll have less than a dozen types rather than more than a hundred. That makes a huge difference. In that circumstance then you might rightly expect to have a set of rules with few or no exceptions.

There’s a lot to be said for “Special rules done well”.

If you can restrict your stat-line to five elements plus a special then most players will have enough surplus braincells to fully experience the game.

Pulp Alley does special rules extremely well. Each character in your league (Typically 6 or 7 strong) has six stats – probably two which stand out form the herd, and on or two special rules. The game has masses of special rules – about 6 pages of lists. Sounds like a nightmare-right? It would be except most specials are one liners that merge into the stat line: “Sharpshooter – the character gains an extra shooting die”. “Tough – the character moves up one hit die” – Most of the specials apply directly to the stat line, and don’t require a ton of rule checking during play.

Middling I’d put Black Powder: Again around 6 stats per unit plus any number of specials. A few of these modify the stat line, but more provide a plus in certain combat situations. Some of them are remarkably similar, and could easily have been merged: One that allows re-rolling a single miss, and another that rolls and extra die (Same effect unless all the first shots hit).

Poor: I hate fingering Hail Caesar. It’s very similar to Black Powder, but the variety of Ancient warfare creates a longer list of specials. It becomes unmanagable with certain favoured troops (Roman legionaries get five specials, each of which is a situational modifier to their stat line). It’s all to easy to forget in teh geat of adding up the modifiers.

Check out Pulp Alley – You may never wish to play a pulp setting, but the rules are a great example of economical writing, and well integrated mechanisms.

Pingback: Playtesting Questions |

Pingback: The fifth-edition Dungeon Master’s Guide joins the battle against excessive backstory | DMDavid

Pingback: Tinkering with things that work | The Peoples Projects

Pingback: Frog of War Project Update 2 – Pitter Patter Games

Pingback: Just say No To Mediocrity |

Pingback: Game Design: Double Vision |

Pingback: Making a Board Game – My WordPress