Co-operative play is rather fashionable in game designs at the moment. It comes in a few distinct flavours, and although they can be quite different they all tend to get lumped together into “co-op”. Personally, I like some types and can’t get on with others. I understand how they work, I just find them more frustrating than fun in practice. Of course, I’m not the only one going to be playing the games I design, so I’m happy to include modes I don’t expect to use myself (once I’ve done playtesting) in DKH or other designs. Pure Co-op (see below) is one of those.

First, some definitions.

Definitions

I think there are two main stylistic approaches to co-operative gaming.

Pure Co-op: all players on one side are working towards exactly the same goal and play as a group. Usually they either win or lose collectively, ie all win or all lose.

Semi Co-op: all players are nominally on the same side and are playing for the same overall aim. However, they have significant individual goals as well, and though they may all lose together (if the main aim is not met), they can be ranked individually if their side wins. In other words, they need to co-operate enough to ensure their side’s victory, but also mess with their erstwhile comrades to ensure they beat them too.

Mechanically there is not a lot of difference between the two. In play, however, they are very different.

Either type can be played against a live player or against the game. Either type can include a traitor among the co-op players, secretly working against them. Neither of these variations changes the fundamental way these types work and the fundamental differences between them.

Of course, you may disagree with these definitions, which is fine. However, for the rest of this article I shall assume that they are correct.

My View

Personally, I don’t enjoy Pure Co-op games. Perhaps this is because I’m overly competitive, perhaps I’m just a curmudgeon who doesn’t play nice with others. However, every time I have played one of these games the following happens. Depending on which player you are, either:

- Someone else knows the game better then you do. They tell you what you need to do and so all you are doing is moving the pieces where you’re told to. Help in learning rules is fine and expected in any game. That may happen here too, but it is not the same thing. I don’t find this interesting or fun.

- You know the game better than everyone else. Either you tell them what they need to do (see first bullet point) or you sit and watch them mess things up. Losing because my allies did daft things isn’t fun either.

I find both of these situations extremely frustrating, intellectually stultifying and generally no fun at all. Nor do I relish the choice between meddling with someone else’s enjoyment or losing my own.

Interestingly, this is much the same dynamic I found in group work at university. We were occasionally told to work as a group. We had a set task and were supposed to work together to achieve it. Each person in the group got marked equally, regardless of whether they had actually done anything to help or not. This is great if you are a lazy toad because someone else will almost always take up the slack and you will get the best mark someone else can get for you. As I wasn’t the lazy toad, doing more than my share of the work so that some idiot could get a better grade than he deserved did not sit well. It’s a stupid and entirely unrealistic piece of laziness on the part of the college. All it gains is less marking for the lecturers. Now if people cannot work properly together when something much more important than a game is at stake, how is this a good plan for playing a game?

A Social Activity

Now you may say that face-to-face social interaction is all part of board gaming, and I’d agree entirely. It’s why I’m less of a fan of computer games than board, card or tabletop games: I like dealing with people in person. Even so, I think this takes things too far. Pure Co-op games are, in my view, not always even games at all. Let me explain.

Games are defined a number of ways. The dictionary gives a few broad definitions of the noun game, including “an amusement or pastime”. However, whilst that covers Pure Co-op games it also covers many other things most gamers wouldn’t normally consider to be games. For example, playing practical jokes on people could be described as “an amusement or pastime”, though I wouldn’t really call it a game. The old Samurai habit of watching cherry blossom falling, or leaves floating by on the autumn stream are definitely amusements or pastimes, but hardly games. So I’d suggest that this definition can be safely ignored as too vague to be functional.

The more useful definition of the noun game is “a competitive activity involving skill, chance or endurance on the part of two or more persons who play according to a set of rules…”.¹ The relevant bit for me is the word competitive. Whether or not this is a reasonable definition of game, looking it up crystallised for me what I’d been thinking: that it is simply the lack of competition that causes the problems mentioned above. Competition is so fundamental to gaming that not having it creates problems in knowing how to deal with the result. There is no gamer’s etiquette for how you play without frustrating each other when you’re all on the same side, if indeed that is possible.

As soon as you put back some of the competition (making it Semi-Co-op instead of Pure Co-op) then it all works much better. At least it does for me.

A Family Affair

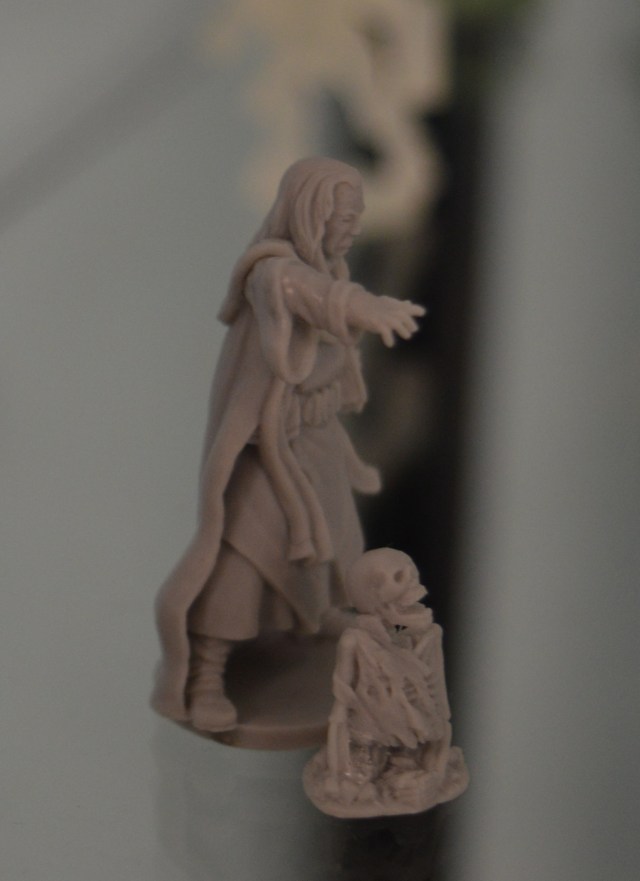

Of course, there is always the cry of the family man. “I want to be able to play the game with my wife and kids”, he says. “They aren’t gamers and won’t play competitive games”. That’s fine, and as I said at the start of this article, I’m happy to accommodate that style too. However, as I also said, I don’t think Pure Co-op games are really games at all – what they are is more akin to performance art or social get-togethers and that’s exactly what you need here. The board, cards miniatures or whatever simply act as a focal point around which the social interaction takes place. If you like, it flips the idea that you have a game with some social interaction and makes it social interaction with a game. Except in my view the act of doing this destroys the game in the process.

What you really need is not so much a game as a social focal point. That could be anything. If you weren’t a gamer then it would probably be something else, and would work just as well as an excuse to share some fun time with your family and friends.

In my many years in the gaming industry and as a gamer long before that, I’ve played with a wide variety of people. I’ve run game demos with everyone from hardcore gamers to bored grandparents, from straight A students to school-skipping street kids (seriously), and with games that were designed for non-gamers as well as those intended for dyed-in-the-wool geeks. For me, the actual game you have in front of you doesn’t matter – what’s important is that people have fun, and you adapt the props you have in front of you accordingly. With “real” gamers, they’ll want to play by the rules. With non-gamers the approach needs to be different.

The typical situation when non-gamers play a game is when one of the group is actually a “real” gamer. Either they are trying to encourage the rest of their family to see what they enjoy about it, bring on the next generation of young gamers, are being humoured by a spouse, or simply want to spend some quality time with the family – the reason isn’t especially important. What is important is understanding that this² is not a normal game in the way that your geek buddies would play it.

I’ll assume for the moment (because you’re reading this) that you are the gamer in question, surrounded by a group of non-gamers who want to play something. You are, in effect, running a demo rather than playing a game. Because you are the gamer you will be expected to know what’s going on. Similarly, it’s your fault if it’s dull. Best avoid that.

To be successful, you need to read what people want, when they’re bored (do less of that), which bits they enjoy (more of that), and generally chivvy the process along so that everyone has a good time. The rules should be ignored as appropriate, ridden roughshod over if required, and amended as necessary. Remember, this isn’t really a game, it’s an entertainment, a show, a spectacle. You’re not a gamer now, you;re the Master of Ceremonies.

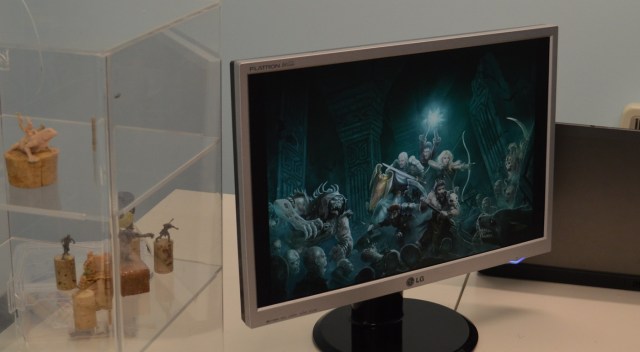

So What About DKH4?

The next DKH will include both Pure Co-op and Semi-Co-op modes of play. Pure Co-op is actually relatively easy to design once you have everything else in place, and as some people want it then I’m happy to give it to them. I think having the variety of play modes is a strength not a weakness.

Now, feel free to tell me that I’m wrong 😉

1: Intriguingly that disallows solo play too, but that’s a discussion for another time.

2: Whatever this is. Like I said, the rules themselves are secondary, although picking something you can explain quickly will help.